Introduction

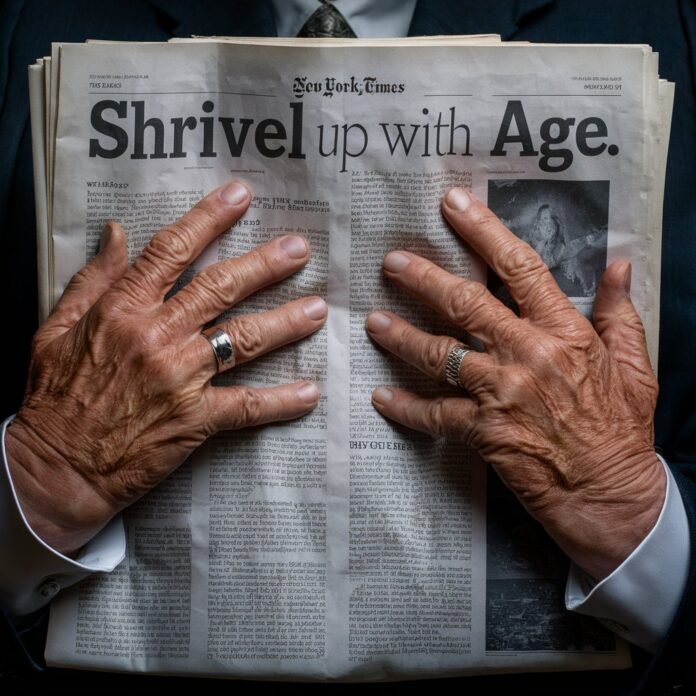

Aging is an inescapable truth, a slow dance between biology and time that leaves its mark on every cell in our bodies. The New York Times has long explored the science, psychology, and cultural perceptions of growing older, revealing both its harsh realities and unexpected beauty. From wrinkles and weakened bones to wisdom and resilience, aging is a paradox—diminishing the physical while often enriching the spirit. But what does it really mean to shrivel up with age? Is it purely a story of decline, or is there a deeper narrative of adaptation and grace? This article unpacks the multifaceted journey of aging, examining its biological mechanisms, societal attitudes, and the ways we can navigate it with dignity and purpose.

1. The Biology of Aging: Why We Wrinkle, Weaken, and Slow Down

Aging is not a single process but a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and cellular factors. Over time, our cells accumulate damage—telomeres shorten, collagen production declines, and oxidative stress takes its toll. The skin loses elasticity, leading to wrinkles; muscles atrophy, reducing strength; and bones become more brittle, increasing fracture risk. The New York Times has reported extensively on breakthroughs in longevity research, from senolytics (drugs that target aging cells) to the role of inflammation in accelerating decline. Yet, despite scientific advances, no miracle cure exists to halt aging entirely. Instead, understanding these biological shifts allows us to mitigate their effects through nutrition, exercise, and preventive healthcare, turning what seems like inevitable decay into a manageable, even dignified, transition.

2. Society’s Double Standard: Youth Worship vs. Respect for Elders

While some cultures revere the elderly for their wisdom, Western society often treats aging as something to be resisted—a problem to be fixed with creams, surgeries, and denial. The NYT has highlighted how ageism permeates workplaces, media, and social interactions, where older individuals are frequently sidelined or stereotyped as out of touch. Yet, there’s a growing counter-movement celebrating aging as a natural, even empowering, phase of life. Publications like The New York Times Magazine have profiled older adults thriving in second careers, activism, and art, challenging the narrative that vitality belongs exclusively to the young. The tension between these perspectives raises critical questions: How can we shift from fearing aging to valuing it? And what would a society look like that truly honors the contributions of its oldest members?

3. The Mental and Emotional Landscape of Growing Older

Aging isn’t just a physical process—it reshapes our minds and emotions in profound ways. Cognitive decline, such as memory lapses or slower processing speed, is a common concern, but research shows that emotional intelligence and resilience often improve with age. The NYT’s wellness sections have explored how older adults report higher levels of contentment, having outgrown the anxieties of youth and learned to prioritize meaningful relationships. However, mental health challenges like loneliness and depression remain prevalent, particularly in societies where elders are isolated. Addressing these issues requires community support, intergenerational connections, and policies that foster inclusion. The psychological journey of aging, then, is not just about loss but about adaptation, offering a chance to redefine purpose and find joy in simplicity.

4. Longevity Hacks: Can We Slow Down the Clock?

From calorie restriction to intermittent fasting, the New York Times has scrutinized countless anti-aging trends, separating fads from science. While no intervention can stop time, certain habits—like regular exercise, a Mediterranean diet, and stress management—have been proven to extend healthspan (the years lived in good health). Cutting-edge research on biomarkers of aging and genetic therapies offers hope for future breakthroughs, but for now, the most effective strategies are refreshingly low-tech: staying socially engaged, keeping the mind active, and cultivating gratitude. The quest for longevity isn’t about chasing immortality; it’s about compressing morbidity to ensure that our later years are vibrant, not just prolonged.

5. Embracing the Inevitable: Redefining Aging on Our Own Terms

Ultimately, aging is a universal experience, yet deeply personal. The NYT’s obituaries and human-interest stories often highlight lives that defied stereotypes—artists creating masterpieces in their 80s, activists fighting for change well past retirement. These narratives remind us that while bodies may shrivel, spirits can expand. The key lies in reframing aging not as a decline but as a continuation, where each phase brings its own rewards. Practical steps—like financial planning, fostering intergenerational bonds, and advocating for age-friendly policies—can help individuals navigate the later years with agency. By confronting aging with curiosity rather than fear, we can write a story that’s not about shrinking, but about deepening.

Conclusion

To shrivel up with age, as explored by The New York Times, is to engage in a profound negotiation between biology and identity. While time undeniably alters our bodies and circumstances, it also offers opportunities for growth, connection, and reinvention. The true measure of aging isn’t in the wrinkles or the slowing gait, but in how we adapt—finding beauty in the patina of experience and strength in the wisdom of years. Perhaps, then, the real headline isn’t about decline at all, but about the resilience that endures long after youth fades.